Ninaivu, meaning ‘to recall’ in Tamil, is meant to be an archival space that the Ilankai/Eelam/Sri Lankan Tamil community can see a pluralistic view of what the Tamil diaspora looks like. This archive focuses on the experiences of Tamil cis women and LGBTQ+ folks, in an effort to change the patriarchal and heteronormative narrative that dominates diasporic conversation.

To see more about this project, please take a look at their Instagram, linked here: https://www.instagram.com/ninaivu_memory_archive/

Also, watch the video of Ninaivu's Launch Event below for even more information on this project! For a version of the video with closed captioning, please click here.

Abhirami Balachandran

So my name is Abhirami Balachandran. Pronouns, are they/them. I was born and raised in Scarborough, Ontario in Canada. I describe myself as second-generation Tamil diasporic. My parents are first generation Tamil diasporic from the island of Sri Lanka or Ilankai or Eelam. My dad’s side is from Batticaloa, which is Eastern Province and then my mom is from the northern province, Jaffna otherwise known as Yalpanam. …In Sri Lanka we were never viewed as part of the nation-state. And I think that's part of just the reason why we all kinda left the island to begin with is because everything Sri Lanka stood for was, was outside of what we were as Tamil people. I won’t say everything, but a good chunk of it was. And, of course, genocide.

There's this one particular memory I have from Grade Two. We all had to draw flags, like the countries that our parents come from. And so I found the Sri Lankan flag and I was like, “Oh my God, this is going to be so hard to do in my journal.” So again, I'm in grade two, I don't really know about the politics of the war or anything like that. But I was excited because I'm like, “I'm going to do this and I'm gonna do this really well.” So I did it. And then the lion is really hard to draw, and I’m trying to figure out how to do it really nicely. And then I finally did it and I'd picked the perfect colors and it looked so good. And I go to my dad and I was like, “Appa! Appa! look what I did at school today!” And he was like, “Throw that out! That’s not even our flag.” And I'm like,” What?! What do you mean? You’re from Sri Lanka and this is our flag!” And he was really upset, like he was visibly upset. And I was just really confused. He didn't take the time to explain this to me and not that he has to, you know, he's also living with his own trauma. I was just distraught because I worked so hard on this and he hated it. But I didn't understand how complex the situation was and I think from then I realized I’m like, “Oh, okay, so Sri Lankan as an identity isn’t something that’s for me.” And honestly, I don't even call myself a Canadian, even though I was born on Canadian soil. Even though I have a Canadian passport and I have access to a lot of things. I still think that Canada as a nation state, is still violent. And you know, with people being all patriotic and being like, “Yeah! I’m Canadian,” which I think a lot of diasporic Tamil people do, which again, complex - because of their trauma. But in saying that [I’m Canadian], I'm also saying that I'm okay with the genocide of Indigenous people on Turtle Island.

I think it was also challenging to navigate because like I mentioned earlier, going into Tamil nationalist spaces as a queer body, I was never going to disclose my queerness because that meant that I'm putting myself at risk. And I just wasn’t in a place in my life where I felt safe or secure enough to leave my house to go and explore my queerness more. So I stayed and I thought maybe this was just the phase that will go away at some point. Not true…it doesn't work like that. I actually brought this up in a podcast episode that I did with "Dash the Curry.” This was around the time of the Orlando shooting. The gay nightclub shooting. And so I was in my living room with my uncle. My Uncle is also very hardcore Tamil nationalist, and we were watching CP 24, which is the local news channel here. They're talking about Pulse nightclub and he was like, “Oh my god, like that’s so sad. I can't believe that this many people died.” And then I'm like, yeah, I can’t believe that it happened at a gay nightclub” and then he was like “Oh, they deserve it.” And I was like, wow, here you are talking about liberation for all Tamil people. And obviously I didn't disclose anything about myself then. I was like: How could you say that? How could you say that someone, because of their queerness, is not deserving of life? And to die a very violent death like that? As a Tamil person who has like experienced genocide? Like how are you able to just be like, “Well, I'm worthy of surviving, but you're not because of your sexuality, because of who you love or who you're attracted to.”

For me this is absurd. So I went off on him. And I think that was the first time I ever spoke back to him and that was a little bit jarring for him. So he apologized immediately. He was just like, “Well, I've never actually seen you this upset. I'm really sorry.” I think in a lot of different ways.... even when I would watch Ellen at home, my dad wouldn't let me because she was queer. And, you know, when there was coverage on Toronto’s Gay Pride parade, my parents would quickly just be like, “Ah! Change it!” Because they're like you can’t be watching that. So it was very much this- very don't ask, don't tell, don't show. One day my mom asked me “Abhirami, what is it in the water here that turns everybody gay?” And I was thinking, “Amma, what the fuck kind of question is that? What?” This was after I came out to her, this must have been like three or four years ago. Yes, so she was very like “Back home we don't really have that” and I'm like, “No, Amma it's not that you don’t have it, it's because people don't feel safe coming out.” Yeah. But that's what I mean, right? Like this idea of being queer and Tamil just doesn't exist in their minds. So when you have visibly queer bodies that are present, and Tamil, and queer. and trying to live their best life. They're always just confused.

And even the idea of …non-binary. [I was told about] None of that. No! No! I was like “Oh, this must make me whitewashed.” When I... when I started to understand a little bit more, my own understanding of transness was through the lens of whiteness. So even then I still felt like I was out of place. I think for a long time, especially when it came to being non-binary, I felt like you had to look more androgynous to consider yourself non-binary. I mean, my hair is short now, I just cut it. But for a very long time, I was non-binary and presented a lot more femme. And that... that only happened because I started meeting more people who were non-binary and femme. When I first started seeing more mainstrean representations of non-binaryness, it was always thin, white, androgynous, assigned female at birth...people who look like Ruby Rose. That’s what I thought being non-binary was. And so I think a lot of my queerness, and the stepping stones of my queerness were built on whiteness and viewing white queerness as the default. And so it wasn't until I started meeting queer people of color that I was like, oh, there's a whole world outside of it that doesn't need to be informed by or center whiteness.

Darshika S.

My name is Darshika and I live in Toronto, Canada…more specifically a community called Scarborough. I've lived across the city for many years and in various spaces, but I often identify Scarborough as home. I identify as Eelam Tamil. I locate myself as a settler on Indigenous land. And in that way I complicate my identity on this land and I think that my existence and my identity is implicated…and it is implicated in my settler colony on Turtle Island, which is how I recognize this land. And it's my responsibility that in everything that I do, to my best ability, that I am conscious of my responsibility… conscious and active in my solidarity with Indigenous people. So that's how I locate myself and my ethnicity.

I think that we have to understand what that Eelam Tamil identity is or what Tamil Eelam is… we have to date back to a pre-colonial time where there was the Tamil kingdom and the Sinhala kingdom. We existed as autonomous kingdoms and lands, and the political boundaries and the ideological boundaries of Tamil Eelam are set by …I believe they said when somebody asked, “Where is Tamil Eelam?” They said, “Take a map and trace out every single place that has been bombed. And, massacres conducted by the Sri Lankan government. If you trace out that map, that is, that is Tamil Eelam, you will see Tamil Eelam.” I thought that resonated deeply with me. I can't remember who said it, but it's unknown to me, so I do want to verify the fact that those aren't my words. And so, I think that for me, Tamil Eelam is a political, ideological, social, and economic, geopolitical boundary. But it's also an idea of what space and safety mean to me. It's implicated in the way that my migration story or my family's migration story and my lived experiences have… evolved. Because I sit…as a settler on this land and recognize the fact that British colonialism and settler colonialism are implicated in the, in the genocide, ongoing genocide of Indigenous people in this land. In the same way that I am indigenous to Tamil Eelam. British and settler colonialism is implicated and continues to be implicated through Sinhala chauvinism and Buddhist nationalism in the violence of our homeland. …

I think it's also important to recognize that protests that are happening in India with the farmers' protest on the upsurge and just international attention to that…along with the Black Lives Matter movement, so many movements, colonization and imperialism continue to manifest themselves in many ways. And I think that it's interesting because…I saw a quote on Twitter that somebody had sent out. I think he's an elected official in England perhaps. But he said [something like], those who say that… people should not get involved as a diaspora in what is happening in the Northeast of [India] or Tamil Eelam. Or those who are involved like that. If we follow that logic, then nobody outside of Germany should have been involved in the Nazi, in fighting the Nazis during the Holocaust of Jews. Nobody should, internationally, we should not have been involved when fighting South African apartheid at the hands of the Afrikaners. We should not have been involved in fighting anti-Black racism in the United States, internationally. Our bodies are not limited to boundaries and our lived experiences are very connected to that. And so I think that logic is flawed…that’s my personal opinion and my political opinion. So, so that's how I implicate my identity and how I locate myself…as an immigrant, as a settler and a woman…cisgendered woman and an Eelam Tamil feminist.

I think for me, if I don't identify as [Sri Lankan] because I think both nation-state boundaries are also constructed…because I think those identities are constructed and the boundaries of Sri Lanka are constructed. In my mind, Sri Lanka as a nation state deserves to exist as much as Tamil Eelam deserves to exist. And in Tamil Eelam, I believe that Sinhalese, Tamil… all languages should…people should have the liberty to speak all languages…Ethno-nationalism, as in Tamil ethno-nationalism, I understand it because it is a response to Sinhala Buddha chauvinism. That's what people often are like, “Oh, ethno-nationalism is not the answer!” Yes, I understand that it has toxic elements to it, but it's a response to Sinhala Buddha chauvinism… and the fear mongering, dehumanization of it. And so it will continue to exist as long as the state continues to eradicate and eliminate Tamil people on the island. There is power implicated in there…Because the Tamil liberation struggle occurred long before the start…60 years before… independence of Sri Lanka. And before that we were talking about liberation. And then after independence it continued through satyagraha and peaceful resistance. And you know, Gandhian methodologies of… protests and civil disobedience and then evolved into an armed struggle because people couldn't take it anymore… and that’s when the LTTE and so many other armed groups evolved. And that's a different history…that’s a whole history. But I think in context, I think for me, it's important to identify and locate the violence. And that's how I name it. And I think by verbalizing and identifying myself, a being as a body… I become… my body becomes resistant… My existence is resistance.

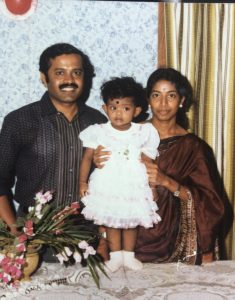

[My parents] never spoke about it. There's the photo that I sent … That was my first birthday. I was born during the 1983 riots…and my parents talk about that a lot. And my dad talks about how he, this is his story, but how he, when he realized he was no longer Sri Lankan, that this no longer was his land… and believing in the resistance movement. Because, my dad, he had quite a bit of privilege back home…and he still resonates with that. And there's a lot of, you know, caste privilege involved in that and denial. And he often says, when he went into work and was questioned by the Sri Lankan government for being at the bank. Because he was called into the bank to withdraw gold and give it out to people… because they had heard that the Tigers were coming. Because it's a government bank and that's the Jaffna branch. And he remembers dropping to the ground and gunfire….and just not knowing if he was going to see us again. And then he remembers him and another Tamil boy were taken outside by the…the Sri Lankan army. And he was asked who gave information to the Tigers, it was the two Tamils in the [Bank] branch that were questioned. And they later took the boy because they had identified …that he did or at least they let my dad go… for whatever reason. But he realized….he said at that point, he knew this was no longer his home anymore…and he said that he knew he had to leave and to give me a better future. And he knew that in my lifetime this problem wasn't going to come to an end. So he decided to leave…and he left first and then my mom and I followed after, when I was two.

D’Lo

My name is… D’Lo, I go by he or they. I live in Santa Monica, California. I am on Tongva land, and I was raised in Lancaster, California, and that is Paiute land. And I was born in Queens, New York. I'm Tamil Sri Lankan American. The identification as Tamil and Sri Lankan… the way that I kind of see it, is because my parents came to the States pre [Sri Lankan Civil] war and… our Tamil community was mostly created by doctors, so these are all Jaffna akkal who came and then … they did their all island exam, came to the East Coast, did residencies and then came to Lancaster [California]. There's a long sort of interesting, beautiful story or not long… But just as far as, the migration to this very hick, racist town on the West Coast. That's an hour away from Los Angeles, but it was very white and hick and country. We didn't even have stop lights. You know what I'm saying? Just a bunch of stop signs everywhere, if that. Now, it's developed into, a sort of bustling, smaller city. But, growing up, it was very hick.

So I kind of say that about my background to sort of say we came during a time that the timing was privilege and the situation was privileged. In Toronto, people identify as Tamil and knock off the Sri Lankan altogether because … the Sri Lankaness is related to the Sri Lankan government or being Singhalese and all the discrimination and the nationalism, genocide, racism, et cetera, et cetera. So for us, we didn’t… feel that in the same sort of regard. I tell people that our community was very pro Tiger, in the eighties and throughout the nineties, I believe. But we were an older community that migrated and so the connections were different. So, we might have come in the late seventies, early eighties, but then, once people started sponsoring their relatives to come, that was sort of when things got a little bit more nuanced. And our community grew and I think Tamilness and Hinduness ended up becoming big points of holding onto something; But still, we said Sri Lankan. And I think for us, it was to say Sri Lankan meant that we were very clear that we weren't Indian. And that there was an island out there, that might not want us, but there was an island that we considered our motherland. I was talking to my cousin and he says that he’s Sri Lankan Tamil to differentiate from Indian. And I say Tamil Sri Lankan and I don't even care if people…the Sri Lankan part was important for me, because it was… you're going to have to know all of this by me saying Tamil. I am now using Tamil to say who I am. And it's so funny, because it'll be like, “Tamil.” and then, a pause… and then Sri Lankan or Tamil from Sri Lanka or something like that. But with Tamil akkal [people], then I will say, “Yeah, I’m Tamil.”

And it was it, I think that because I'm queer… it was sort of like I needed to sort of be seen for my queer identity, because I already had my Tamil identity. The shit that changed for me was… So, in the very beginning of growing up my Appa used to talk to us about what was happening on the island, and then there was also us, knowing that we were in a racist town. So, it was like, okay, well, we're not wanted on the island and we're kind of not wanted here. So, just kind of understanding… the messaging that was being absorbed was that we needed to lay low. Not kick up any dust and just kind of chill…my queerness fucked that all up, right? But, you know, I realized more and more [that]my parents... their whole way of survival was staying quiet. And there's a privilege with staying quiet too...you can afford to stay quiet and then. In some ways they would act against racism, but... what I'm saying is that they weren't loud and vocal. I was being mentored by queer and sort of communist activists and feminists. Coming into my queer skin more, I felt like there was no space for me to sort of own that moment because I felt like everything about my queerness was not being seen by the Tamil community and was actually trying to be silenced. There were so many fights about what I was [performing] because I was also talking about being queer on stage and that was the, “Why do you need to tell people?” But I think that because I was queer, they were almost only concentrating on my queerness and not necessarily my career or how I was doing. And then you get to a certain age, and you're just like, I can't give a fuck anymore If I'm going to be sane, I can’t have them be the center of everything. I'm still learning the lessons of not centering other people before me, this is a lifelong lesson. I think that the best part of being able to have a somewhat successful artistic career, has been that nobody could say shit. It's on their terms, they wouldn't say shit. That's the equation that they've come up with, you know…Nobody knows anybody in the artistic field. You know what I'm saying, that they can just be like, hey, you know, so I think that it's more about a skill set. It's like, oh, be a doctor because we know so many and you'll be helped every step of the way or be a lawyer. If my kid wanted to go into the arts, they would have all of the skills to sort of help them mentally and I think that that's really what it is. It's not being able to offer anybody [help], so then there's the sphere of the unknown. There's also the other part about it is that, like, if you are doing art… there's that respectability politics. Do Carnatic singing or do this …I don't get mad at the community for not pushing people in the arts. I think that it's, like, don't you don't need to push us, but just don't get in the fucking way. If we're saying we want to do something, don't say don't do it.

Anything to do with Sri Lanka...I know my lane is two people... my friend Nimmi and Yal. So that's what I attach my work focus to... because there's already an infrastructure there. But the work that I've done in Sri Lanka was the reason....they need folks to come out there and just hang out and build community with. So many people were like, “We thought you all forgot us.” That makes me feel so emotional, because I'm like, yeah, of course, you would. You know, nobody...the people who could afford to get off the island, or the people who could get off the island… And then the people who are left by choice or usually, not by choice. [They’re] like,“Where have you all been at?” I think that it resonates so deeply to me, because to believe that you've been forgotten is is a queer story… so I, get it completely. Every time I go back to Sri Lanka, and I'm talking with Tamil people. I'm just like, “Why are we not doing this and what can I do?” Now, as a sole person I don't have the time and the space to actually spearhead something so, anything that is happening already I try to be a resource and I also try and get money to make the thing happen. Yeah, so that's kind of my role right now, as I'm trying to get other stuff off the ground. Being allies and centering their shit, you know what I'm saying? There's so much cockiness in our diaspora, politically. And we don't know anything. We have a lot of baggage and trauma and that is what is informing how we are. There are women and queer people...just so many people who are just down and they can do it… over there. The best work that we can do, if we're really trying to work, is to listen. Just shut up and listen. Then ask, “What is it that you need?” I feel is a tried and true method for support. Tamillness [to me]is being brown... of a specific feel. It’s about an understanding of land and an understanding of stolen land. It's about understanding the preciousness of life… and that it can go at any moment. And it's an understanding of people who are deeply loved and yet deeply hated. I think there's a lot of good with the bad... in regards to my queerness, as we've been talking… Do I wish my people were better? Yeah. Do I know that we have a lot of trauma? Yes. I think that Tamil pride, to me, is… I want Tamil pride to mean queer, brown pride. Tamil pride… when it's not inclusive, is something that I’m scared of.

Faith Rajasingham

[My name is] Faith Rajasingham. I am from Toronto, Canada. I am Eelam Tamil, so I would like to be referred to that way. I go by the pronouns she/her. So I grew up with a very strong Tamil identity at home. Then obviously during the 2008-2009 protests that were going on here in Canada, as well as just everything that was happening globally… my family was very much involved with the protests. And so we went to all of the places, we would take weekend driving trips down to Washington D.C. and everything. And I started… I started questioning just generally, within myself, the idea of labeling myself as Sri Lankan. Before that, yeah, I did take on the Sri Lankan identity when people would ask me “Where I’m from?” Never really questioned it before, but during that time period, started slowly questioning it. And then I remember having conversations with my non-Tamil classmates in elementary school and high school, and just kind of identifying myself as I am Eelam Tamil. Slowly, I would identify myself as Eelam Tamil, but I would mix it with Sri Lankan Tamil identity. And then once I got into university… I became a lot more politically involved on campus and off campus. And so with that, I had to make that decision of how will I be identifying myself, right? Because your identity is also how you lead yourself and how you present yourself to the world. So I made that conscious decision to only go by Eelam Tamil during my first year, maybe my second year… Some time around then. So that was 2014…2015-ish. And ever since then, I've just only identified myself as Eelam Tamil.

I know when as children, asking my parents about our homeland and anything…Yeah, they use Sri Lanka a lot because it's just a common geopolitical border that everyone referred to internationally. And that's the place that everyone knew it as, but they would also use Ceylon, they’d use Ilankai, Yalpanam. So these are definitely labels, words, that I also kind of relearn because I used them interchangeably. But only now, I'm learning that they have very specific designations to these identities and geographies. But then again during the protest time was when we, as a family, started identifying ourselves as Eelam Tamil. Anytime it was an Eelam Tamil issue that came up, my parents were very proud to identify themselves as Eelam Tamil. So I guess, because, definitely during that university time period I personally realized that there was such an important history that we have with the idea of Eelam and our own liberation movement. And so identifying us specifically, or I, myself specifically as Eelam Tamil it is, it's an act of resistance really. It is in memory of all of the people who gave up their lives, all of our maaveerar, everyone that gave up their lives for us, all of the people even who survived during the war. And so just remembering everything that our people have to go through. Our history is very different from Indian Tamil, Malaysian Tamil, Singapore Tamils. Even the Canadian Tamil identity is very Eelam Tamil really, because we have such a [large] diaspora in Canada from Eelam. And so yeah, I think for me it was very much, you know, like remembering, honoring, and being that active resistance.

My elementary school... didn't have a lot of just generally Tamil people, it had a lot of Filipinos actually. So I grew up around a lot of Filipinos. And then in high school I was in [an] upper middle-class [area], a lot of white girls, it was an all girls school. Then in University, the university that I went to actually has the biggest South Asian population in Toronto University. So yeah, super interesting with those kinds of fluctuations that I went through growing up. So we do have a lot, I would say, small ethnic stories…a lot of bakeries and a lot of fast food places you can go to. It makes such a big difference because it, food, obviously as we know, is kind of the biggest vein which people can connect to culture and to our own culture and heritage. And so being able to go to Tamil grocery stores and pick up our own vegetables and fruits and ingredients, and then even going with my Mom and Dad every Saturday morning. And so it's the type of knowledge that I would say I'm very privileged to have access to otherwise, I know a lot of kids….might not have had that same experience. I can also speak to experiences of my friends who grew up in very Tamil dominated areas and with a lot of Tamil kids at school. And we have these stereotypes of certain schools being like, oh, that's a Tamil school…that’s where all the Tamil kids go to. So it’s… it's kinda cool because you show these pockets of neighborhoods that are very much dominated by people. And of course, the immigration base influences that too, but definitely influenced almost every aspect of my life.

So I know my mom is from Tellippalai, which is considered one of the Jaffna villages… When she was in her early twenties, that was when the Indian army was trying to pillage the neighboring villages, so she and her aunt and her cousin escaped and they moved to Colombo for some time. And my dad was born and raised in Colombo, but his grandfather is originally from Jaffna on his mother's side, on my [grandfather’s] side they’re from the …Eastern region. My dad's grandfather had money because he worked in Dubai for quite a long time. And so with that money that he had, he migrated to The States, actually, in the nineties. I think early, early nineties. And he kinda saw the situation and hated it, and he decided this is not the place. He then crossed over to Canada, undocumented and once he came over undocumented he then claimed refugee status . And there was a policy going on at the time in Canada, I think this was a policy introduced by Pierre Trudeau, who is our current Prime Minister’ father. It's called The Multiculturalism Act. So I think it allowed a lot of Tamil people to claim refugee status. And so my grandfather was able to get his case heard and he claimed status. My dad was just explaining to us, it’s a bit complicated, because my grandfather tried to put a sponsorship for his kids and his wife. But they were kind of like the last batch of people that were able to be sponsored in this particular fashion. So my dad and his siblings and his mom almost did not get through because there was a lot of paperwork that went kind of on the government side, it got lost or something happened to it. And so for many years, no one really knew [their] status. And so at this point, my mom and dad, I believe they were engaged. My dad was about thirty and my mom was twenty-nine. I think eventually my grandfather was able to get in contact with some local MPP or some local politicians and get his case heard for his family. It was only because of that, they were able to come through as sponsored residents. I think [my parents] got a fast wedding in order to get the sponsorship. I think that's how that happened. I believe there was a small portion right before that, when my dad and his mom went back to Jaffna. And then I think right after the ’83 riots happened, they moved back to Colombo and then that's when the migration process began. Yeah, my parents always told me [they migrated] because of the war. They always said yeah, because of the war. Like, we couldn’t have access to education, they didn’t have access to a lot of basic rights. And so our best option was to leave.

So I am a history major and got an MA in History. I was actually for the longest time on the road to pursue a PhD in History as well. And of course, I wanted to look at Tamil history in Toronto itself. So for my MA, I took a very intersectional approach, maybe a bit more Sociology based than History based. But it was definitely looking at memory, geography, formations and how we even map kin and family in the diaspora itself. And so it was a very fun and super challenging piece to try and evolve. And so for my PhD, then, I wanted to look at Tamil workers in the food industry here in Toronto. Like I mentioned, food is such a big thing and you have such a big Eelam Tamil population, that any restaurant you go to, regardless of the ethnicity or the type of cuisine that's being cooked, you will find many Tamil men working in the kitchens. That is just almost a given fact, like anywhere with good food has Tamil men working in the kitchen. Then, all the Tim Horton's coffee places, all of them have Tamil aunties on the front line. Definitely the food industry is a big win for our people to kind of gain capital here. So I wanted to look at that and understand the formations behind that. Yeah, then life happened and so I had to give up that dream for a little bit. I might go back to it later, but for now, I'm not going for a PhD. But in terms of my career track, I'm still in the history field. I'm currently working… at this museum it's super local, but doing the work that I do and with the identity that I hold I very much come from a very decolonial lens, a very anti oppression lens. And so everything I do at the museum comes with that. And so I help with program planning, a little bit of policy development within the city of Toronto and like a lot of tour guiding and research for the museum. And [within] all of this, I make sure that I come from a very decolonial anti-oppression lens. And that, that's just from me, like being in these spaces and doing what I did all these years. It's just ingrained into me at this point, but that's what I'm gonna do.

Maya McCoy

[My name is] Maya McCoy. [I am] Ilankai (Sri Lankan) Tamil American. Nobody in my family identifies as Ilankai Tamil...I mean that I know of, I guess most people just say Sri Lankan Tamil. But after living on the island and doing some political education around where the term Sri Lanka comes from... I just prefer Ilankai. At least in describing myself, I think I don't mind if other people say...call me Sri Lankan. [Ilankai Tamil] was not used in my home at all. Or really other social situations, except for maybe organizing spaces where we were discussing identity more specifically. I guess I don't know that I would call what I did on the island political education... I was there on a fellowship and it was all diaspora folks. And a lot of different ethnicities, so… we had mixed folks, but also Sinhala folks, Muslim, Tamil. I think we just, internally, had a lot of conversations about how we identified. But, it wasn't until I got, I actually got back from Sri Lanka to the States that… I… was just more in community with other Tamil folks. I didn't really meet that many Tamil people in Colombo. I think while I was there, I learned about the Sinhala Buddhist history… I also did more of that when I got back. I didn't really know that there were diaspora folks who identified as anything other than Sri Lankan until that time. I'd say pretty much all of it was new.

Growing up... I lived in Ohio and also partially coming from a mixed race family, but also just geographically...definitely didn't have a big Sri Lankan community or Tamil community. So, I didn't… I barely even knew that there was a Muslim population on the island and...there's just so much that I had no idea about until I actually got there. I had never heard a word of Sinhala spoken in, in my whole life. And then I took classes in Sinhala while I was there… I would say pretty much everything was new. I turned twenty-three while I was there. It was really interesting...I had only been to the island once when I was seven or eight. So, I think both being able to encounter a lot of these... Obviously, the context was different post-war, but also just as an adult and without my family. I think I went in kind of expecting like, “Oh, I'll have some big clarifying moment about my identity and everything will make sense!” I definitely feel...I understand better where I fit, I guess, within South Asian narratives… but I also, very much left with more questions than answers. I think the biggest thing was just having a diaspora community that's actually global and have really varied experiences. And otherwise I, I just would never have formed those close relationships, so, I think that was the biggest takeaway for sure.

Before I got to college, I also didn't have... not only did I not have Sri Lankan community I didn't have South Asian friends or South Asian American friends and so... once I got to college, I think I was like, “Oh, my gosh!” There's a South Asian Society there are other people here. But I think, those spaces were often pretty Indo-centric and...definitely people were relating on a lot of South Asian cultural things that I was like, “Do I not understand this because I am half white? Do I not understand this because I'm Sri Lankan? Why have I never encountered any of these things before?” I think actually going to the island and understanding a bit better the nuanced difference... South Asia is not a monolith. There's so much diversity, even on the island.

And so to then think about how reductive often the South Asian spaces I had previously been a part of were, I think that was helpful for me just to clarify that. It wasn't like I should have known all of these other things about North Indian… Hindi movie, whatever it is… it just genuinely wasn't a part of my culture. And also, I think it clarified that my family's culture is enough. Just because I went to the island and now know more about the place, that doesn't mean that before I had a less authentic relationship to any part of it.

I think definitely my parents...there was open conversation about the fact that it's clear that my parents are from very different places. Especially having a white dad who was often the person to drop us off at school and be at all the things. So, I think growing up, I was pretty hyper-aware that this is different from a lot of other families. But my first cousins are also half white and so it was both very clear that it wasn't the norm, but [that] in our family it was. So I didn't really think about what it would be like to have two Sri Lankan parents or two Tamil parents. I didn't have those thoughts about what would be different about growing up… Until I got to maybe high school or college, and I was like, “oh, people have these big South Asian communities, and I don't. People know these languages and I don't.” I have one friend who I was on the island with, and he was the only other Tamil person in our little fellowship group, but he was from Scarborough. So he grew up surrounded by community and food and all of it. But his family's Catholic and he has a really white name despite not looking white. He and I would have a lot of conversations about whether we were authentic enough. Even if having participated in this program that was supposedly about a pluralistic vision for the island... Does that mean we're ...where do we see ourselves and everything? And I think one of the things that was really helpful, in talking to him about it... was just realizing that there are so many different experiences and just because my family was privileged in these ways and generationally farther removed. Everybody has these questions about what is authentic and ...do I fit this criteria? And I think the most powerful experiences that I had with my own identity were so much smaller than that. Like going to church in Columbo with my aunt and uncle who lived really close to where I lived and having them introduce me as Ernest Champion’s granddaughter who's here from the States and sitting through a church service in Tamil and not understanding anything. Then having my uncle buy me short-eats after, because he felt bad for me. Those are the things that end up being most meaningful.

Roshni Raveenthiran

So my name is Roshni Raveenthiran and I'm currently living in Toronto, Ontario… specifically Concord. I say that I'm Tamil as the first thing if somebody asks me, if I'm outside of Toronto then I will say I'm from Toronto. I think like I always called myself Indian-Sri Lankan growing up, that’s because I didn't really know the concept of being proud of being Tamil. It was pretty much assimilation and such. But I loved Tamil culture…I consumed the movies, I consumed the language at home, the food, the traditions…it was so Tamil. But also growing up in a very diverse community, I then went into a more predominantly Caucasian or white community …where the concept of ‘brownness’ is either Indian or very South Asian, and then you have the derogatory terms that are being used. Already there's this bad connotation of being brown, so now specifically talking about Tamil, that's an [another] identity that people have no clue about. So it wasn’t until university, post-secondary, where I really was invested in my culture and I knew so much and I learned so much. Then I started learning about my Tamil identity and there's more clarity around it now.

So when I went [to university]… you always do research about school/university beforehand. So I did research not only about the academic portion, but the York Life. When I was in Grade 12, I was very curious…in Grade 11 I had a lot of political conversations or social conversations in my high school. I was talking about, “No, I’m Tamil.” I had those concepts growing up… it was a very liberal and feminist framework. It wasn't as in-depth [in] analysis, was not really community organized… it was just what I know, and my experiences. So when I got into university, I did that research… [asking] what's York Life like? That was the university I went to, and it was the most political campus in the GTA (Greater Toronto Area). It fostered a lot of activists, it fostered a lot of student movements, so you're bound to be in that type of space. And when I went in, you would always be surrounded by protests and political campaigns, and the Student Union there was also highly political. A lot of my mentors came out of the student movement. A lot of Tamil people, a lot of Eelam people in particular, were in the Student Union representing this campus that has fifty-five thousand undergraduate students at a high level. So I got very involved just seeing these people and then also your university classes teach you a lot about in depth frameworks about gender and politics and activism. The Tamil Student Association there pulls out these big events, whether it's pub nights or formals…we have all these great things and I started going to them. But I would go in with my Italian friend, and she was my only friend, I had no Tamil friends. I wasn't invested in it, this is such a culture shock for me. So when I went in, I just went to these events first…until I went to one of their political events. It was a coffee shop, and it was basically talking about different issues about the Tamil identity. I was honest about them… I was like, “I have no clue what the revolution was about. I have no clue of what the Tigers are about. I have no clue what this is, but this is great and I call myself Indian and Sri Lankan.” And I was honest about that. Now, if I was invested in that space longer than I was, and [at the time] I didn't know all the issues that were in organizing, I would've been so scared to say it. Say that I'm Indian- Sri Lankan, because it felt intimidating, it was an intimidating space.

At that time, six years ago, sharing your nuances of identity could foster different perspectives of people. [The space] was also dominated by men who force a political identity on you…that you need to still foster. So there's a lot of issues in there too, but a lot of great organizing that happened that were also led by women and queer folks. So I think that's super dope. But after that coffee shop, I was like, “Holy crap this is like something so cool!” I was invested in my identity. Since then, I did not call myself Indian or Sri Lankan, I said Tamil. And so now I have this, well established… but still growing…once somebody asks you, “what's your background” I say I’m Tamil and that I’m from Toronto. Still as a settler, but from Toronto. I think, [at the coffee shop], it was the conversations that I had with people because… there were also communities that were non-Tamil there that shared their own identities. Whether it's from Palestine or whether it's from folks from Kurdistan to Somalia. So there was a different range of identities and a lot of people who are very vocal about their own genocides that happened in their home country and their liberation. It was like a solidarity conversation as well. I think it just made sense… as soon as people started talking about it. I was like, “Oh my gosh, where was I?” And then I guess me just being a very curious person and me being very passionate about social justice…if I didn't agree with this, then it just wouldn't make sense to my principles. So I went [to] learn more about it. So I read books, I looked at different panels. I talked to a lot of people, a lot of activists, and I got very engaged at my university. I was very involved in the Student Union, I was the Vice President of Equity at a point [during] my last year. And representing… [being] a very political person on campus with a high climate…. you are forced to learn your identity very quickly. And so I think it just made sense and it altered my path completely. I was going to go into clinical psychology and become a psychologist. And now I just shift to mastering my social work and doing community organizing. I think it just made sense to me, and makes you look more into your history.

Growing up, a lot of people who get into these activist spaces are young people. I was exposed to a lot of these activists on campus, I guess at the age of seventeen. So from seventeen-years-old, being curious and then being actively involved at the age of nineteen, you invest a lot. I think learning everything, reading these books, just looking and investing in the spaces kind of really helped me. But it was almost like pressure, right? Because of the role you have power…and there are so many students, so many communities, that you have to advocate for. You also need to fight against right-wing, racist, homophobic people on campus. So you have to be on the ground, you also have to be on campus, you also have to fight against administration. You have to fight against people…literally I remember doing protests and people will take pictures of us and put us on websites and call us terrorists. There was a pressure to advocate for students on campus, but to also keep them safe.

As a child you have these like talks with your parents, and I just had an understanding that something went wrong. Also when anybody talks about Sri Lanka at that time it was war or Tigers. Stimuli comes in often, whether it's from the news, whether it's people …or whether it's your dad talking about it with his friends. You know, my father also went back home during the de facto state..very close to the cease fire, about that time he came back. So I knew those nuances, but I never considered it because of my lived experiences as a Tamil person…in Toronto, there are so many things going on that I had to prioritize [those things] before actually investing in my identity. And so it was not like I was even in this space to learn about these things. Because my dad also wasn't there, predominantly, to teach it. So, what do I look at? When it comes to war …nobody wants to agree with violence or suicide or war… Nobody wants that. But in regards to the situation, armed resistance had to make sense and it was the choice of these women and men to commit to the struggle for their people. So as choices that were made for themselves. So I think you should start learning about it. And then… we live in a world full of war all the time that is caused by [countries like The States] as the number one spear header. And I never rejected things. And so when you learn about it…it was obviously not easy talking about suicide bombings because these woman and man could be part of your ancestry… Just people in this situation, for something that was out of their choice. The violence against Tamil people in Sri Lanka was out of their choice. So it's not easy, it's never easy to think about those things, but you just make sense of it and talk about it.

I think it was awfully hard because I felt…during the situation there were a lot of men who obviously abused power. You have hierarchy, you have patriarchy, you have misogyny. So these are the issues that were happening in our community. And at that time, a lot of men took hold of these spaces. A lot of, you know, uncles, elders. And the community who had a lot to say of what you need to be in this time, put a lot of pressure on me. I don't like people telling me what to do. But I also don't like this very paternal energy on campus, it was just something that felt off. So there's, so there's a lot to it…even with identities, particularly my mom is from Tamil Nadu [India] and my dad is from Eelam, particularly Jaffna. And that, in itself, felt like an identity crisis because no one's really used to the Tamil Nadu, Chennai experience…unless they have family… or from movies. So cinema, which was highly invested in the diaspora. People saw Chennai Tamils or people from Tamil Nadu, through cinema mostly instead of [actually meeting] someone. Because I [did not have] a strong relationship with my father, that Eelam Tamil identity was not constructed properly on that side, but more in school… well, I kinda code switched within the space. But nobody really talked too [about] it until, you know, there were just the snarky comments…It didn't really pissed me off, but it obviously affects your mood. And so there are so many identities, but we kinda forced them to talk about it… as new Tamil people enter these spaces, they kind of challenge the status quo of what they know. We kind of burst their bubble… like “Hi! Not everyone lives where you live. Not everyone is rich. Not everyone is educated about the struggle.” That, itself, was another identity. I think the killer one… is that you needed to know about the struggle since you were born. Not everyone knows about it, not everyone knows about the flag. And the reality is, people are learning it when they go into university. But again, the timeline has changed… from what happened back then till now. Now during this time, there are so many conversations and spaces and platforms that social media has opened as well… to sharing about different identities of what Tamilness is. It's been like a breath of fresh air, because organizing these spaces in Toronto, at that time, was so trapping…. because it's like you were forced to be this very political person. You're forced to know so much. But it's also, we kind of police which identity we can accept. And now I feel there's more of a concrete understanding of “Hey! Don’t be an asshole.” We’ve come a long way, and I think we're still growing [in terms of] policing what Tamil culture is. But now it's getting so much better.

Sharika Thiranagama

[My name is] Sharika Thiranagama, I am currently located in the Bay Area. I have actually always identified Tamil. I use myself often as a test case when I teach my students about ethnicity and violence. I use myself as a test case to show how I know that ethnicity is historically constructed. I teach the history of how certain distinctions became salient and invested in as ethnic identities and others did not. And yet I feel this very strong attachment to being Tamil. And I say, that's what it's about… there’s that sense of attachment. It's a very powerful feeling for people, and you can feel very real and powerful for somebody like me even as I know the history of it. And that is the tangle, really, in ethnic identity in Sri Lanka. I never doubted that I was Tamil, even though my father is Sinhalese. Being mixed... half Sinhalese and half Tamil, or half Muslim and half Tamil...it actually used to be quite common, at least, more than people like to say. What that means, being mixed, has changed over time.

My father was never that bothered for us to be Sinhalese in order for him to be our father. I think that's a more unusual idea in terms of a dominant identity. We grew up with our mother, in our mother’s home in Northern Jaffna with our Tamil family, we spoke Tamil, we thought of ourselves as Tamil. My Sinhalese father also thought of us as Tamil, but it didn't make him not our father. My father’s family, they would come up to Jaffna to visit my mother's mother….they also didn't worry about us being Tamil, I think it was because my father set the tone. So I’ve never really thought of myself as Sinhalese, because I don't speak Sinhalese, even though I have Sinhalese family. I didn't grow up in the South, my Sri Lankan life was almost entirely in the North. My father never spoke Sinhalese to us, he never taught us anything either, and talked to us in a mixture of English and Tamil. Growing up in Sri Lanka... and also from the family that I come from, I have not ever doubted who I am. And who I relate to, who my relationships are with and who I want to be in community with. Maybe that's been made possible by also having a mixed family, by growing up in a Tamil family, but also having a Sinhalese family who are working class. So it kind of gets beyond some of the assumptions one also has, and is trying to reckon with nationalism… on all fronts actually. I don't worry much about my Tamil identity...it's a place from where I start. And it's a language that gives me meaning… a place that opens up to other things. It doesn't close me down.

We lived with my mother until I was ten... until she died and then we lived with my father from the age of ten to eighteen. So ten years with either parent... approximately. I'm realizing when I talk, I don't have a problem with authenticity. In the sense that, you know, I'm from a family who have been called ‘traitors.’ And my mother was somebody who was gossiped about continually through her lifetime, and thought of as immoral and indecent. Because first, she was married to a Sinhalese and then she lived with children on her own. She let her friends come in and out of the house, and she did it all in a rural … peri-urban area. Jaffna is definitely not exactly the metropolis of Colombo...so she was gossiped about all the time. In this kind of hagiography now of my mother, post her assassination...what nobody really talks about what it was like to be her as a young woman… a single parent, you know, living in this fairly conservative society in the middle of war. And doing what she thought was right… and being attacked from it continually. She was the one who fought: she fought in the University, she fought with militants, she fought with the Indian army. You know, it was so unpleasant for her at times. But she also had a very strong sense of justice and hope… and she was a very strong feminist. I think that translated into two things, one of them was, for her, was about justice… and a deep commitment to justice. This evolved over her life, so she started off a nationalist and moved beyond that because... her politics were not dogmatic. Politics was for her not only about dogma but actual life, what people wanted and what people needed... she saw the way the militarization was enveloping...the kind of deaths and disappearances. She had to balance this thing… you know, the state, the Sri Lankan state, is bombing us. The Indian Army is occupying us. But the militants, the Tamil militants, the LTTE are also killing us. How do we hope for more for Tamil the community, for the Tamil and Muslim community? How do we hope for more?

And I still very strongly believe in that sense for Tamils and Muslims and Sinhalese deserve more than to be positioned with a choice of either the devil or the deep blue sea. We can have desires and hopes and dreams which are beyond that. My mother knew that she lived within a very conservative society too… she didn't have to politically affiliate with you to fight for your rights. She was very responsive... her politics were about people and very responsive actually listening to what was going on… and trying to find a future. Always like, “Where do we go beyond this? What is it?” So I think that was one thing I really learned. The other thing I really learned from her was that she thought it was really important to be happy as a woman. Not that happiness was possible, but she thought that… she never hid her life from my sister or I. Because she really taught us that there were many ways to be a Tamil woman, and that being a good Tamil woman was not really that much fun. She put on music, she danced....she was often very sad a lot of the time, but she could be very joyful. She got sadder and sadder as the war went on, but she really thought that it was important that she had work...that you had a job that, she did things, that she could enjoy things... that she could choose her relationships. And she really didn't even have to teach that to my sister and I, she just never hid anything from us. And so we grew up not worrying about what we had to be. We saw that she was punished for what she was, because she was killed. And we obviously felt all that punishment because we used to get gossiped about when we went to school, we could hear. But it's a great gift you can give to your children, to teach them… it was very courageous, but she thought that there was more to her as a person than to be somebody who conformed to what other people thought a good Tamil should be. And it didn't interrupt her desire for justice or help or care for other people... that you don't have to pretend.

And so I've always tried to do that, and that's why I don't have a problem with authenticity...in that sense. Because I've always been from a family that's considered inauthentic or a traitor or scandalous or gossipy...but it's also very real. When I go home, I also know that I know a lot of people and, you know, it still feels like home to me. I don't have to have other people affirm my home for me… I know what my home is. So I try to live my Tamilness like that, that it's something that is about expansive openness... and it's not about being a good person by Tamils. And if somebody says to me, “You’re a bad Tamil” I'm like, “Okay, that's fine! You can say that if you want to, what do I care? I’m sure I am, according to you...I probably am!” I once gave a talk in Tamil Studies about Muslim eviction, and a lot of people came just to tell me off. They were like all these old men getting up and saying, “You don't know, young lady! What you're saying is destructive…” And, you know, I'm quite comfortable with that… You know I've lived around lots and lots of Tamils... so I'm perfectly okay about picking out which ones I have more in common with and which ones I don't. So, I've had access by virtue of growing up [in Sri Lankan] to multiple versions of what it means to be Tamil, for many people. So, I think that gives you a certain freedom... to say that you can pick your own path.

Varuni T.

I live in the New York City region, [I identify as] Tamil. It was just what my parents told me. For a while I did want to say Tamil Sri Lankan, because it's different from Tamil Indian. But it was, yeah, it was a journey. Growing up, it was Tamil… until maybe the nineties. Growing up, I felt Tamil Sri Lankan was my ethnicity and that came from both my parents saying that they are both Tamil Sri Lankan. Because I didn't fit into the Tamil Sri Lankan community in America, then I started just calling myself Tamil once I got to college and that allowed me to access the Tamil Indians as a sort of community. Sometimes I say I'm South Asian, but it doesn't feel like an ethnicity… [it] feels more like a region. I think most of my story with my family has been around creating solutions for the Tamil community. My grandfather was a lawyer and a judge in Sri Lanka, my uncle was a lawyer. Both my parents are in the medical field so they weren’t as involved in politics. However, my father did go with his own father all across Sri Lanka, talking about what Sri Lankans at that time called the ‘ethnic problem.’ They were trying to find a more pluralistic solution. But when I got [to the U.S.] the Tamil sangams felt very…We never went because my parents said they're all Tiger supporters. So we never went to the Tamil sangams because my family in Sri Lanka got death threats from the Tigers since the nineties, so it just didn't feel like a safe place to go. Even my family in Jaffna who’re on my mom's side, they were teachers, and also felt threatened and a little bit bullied by the Tigers. So, uh, it was strange to me, even as a teenager, and in my twenties, growing up hearing about these two different experiences. In Sri Lanka this is what's happening to my family there… being threatened or pressured to give money…Worried about, [being] schoolteachers, what if my kids and my students get recruited. They were worried about those kinds of things, whereas here… there was an energy that supported the Tigers. It didn’t feel like a space that was welcoming of these other experiences that my family had.

I was born in Sri Lanka and I left when I was one. And the reasons we left were because of the threat of violence… the difficulty getting milk. My parents thought there'd be more opportunity somewhere else, and I think there was a story where, like, there was some kind of race riots or some kind of riots in the seventies in Colombo and… my family had to protect me while my parents were at work. There were stories like that… it didn’t feel safe to be in Sri Lanka at that time. So we left in 1979 and we went to England for 4 years, outside of London. And even there I didn't feel like we had a big Tamil community. My parents worked a lot and we had my mom's family… a few people that we saw. We moved around a lot for my parents' jobs. So, I didn't know Tamils there, other than family members. Then we came to America when I was five, and we migrated to Lancaster, California. Which actually is a huge Tamil community, but I was only five so I didn't meet everybody really. We were there for three months, I remember going to school and feeling very different…very different. In England when I went to school, I remember these mostly white or British children…they kind of looked at me, like, I was dirty or something. But they would leave me alone. Kind of pass over me or leave me alone. And when I got to California, the kids were very aggressive. They were pulling at my shirt and arms trying to…Like, “I want to be friends with the kid!” or the ‘different kid’. There was, there was a different energy that America, at least the kids had, that was…shockingly different. But also, I still felt like the only brown [kid] in the class. So it wasn't necessarily acceptance, but it was a strange energy that the little 5 year old had. My dad… felt like he would have more opportunities as a doctor in the U.S. He said he felt that because of racism in England, [that] there were few opportunities to move up. And even when he was around the other doctors it was hard to be accepted for the skills he had, so he… his ideal destination, the U.S. to try something new. In the middle of that bouncing around, we did go back to Sri Lanka. I think when I was four, for a few months…I kind of have a good memory of that time. It was a time that I was there, me and my little brother with my aunt, while my parents…my dad, I think, went to America to try to look for jobs. That was the time where I got to go back to Sri Lanka, again, before finally going to America. So there was bouncing around between Sri Lanka, England, Sri Lanka. Maybe England, America, there was some kind of bounce.

Ideally, I do believe in a nationless world, we are members of this planet. I don't know if my own jumping around… how much it affected that belief. But, I think the jumping around was an experience that I always wanted to talk about in school, or with the people around me. When I finally landed in America, we didn't stay in Lancaster, California. We went to this really rural community called York, Pennsylvania. And there was no space to talk about my migration story. So, I constantly felt like I wasn't American enough. Even though I had lived in two different countries by the age of five. I felt like I came with a story, that story, and nobody asked for that story…the teachers, the other kids. So, I felt like that was how [migrating] affected me, but not in terms of the bigger picture of who we all are on this planet. There was a belief that there's just one way to be American and America is number one… and it was very nationalistic, in terms of being American. That’s what they felt proud of. So, they were more interested in, like, “How do I assimilate this one quickly? She hasn't eaten a hamburger. Oh, my gosh. What kind of alien is she??” They push there’s one way to be American and there's one way to be proud of being American. I mean, I was very lucky that the journey I took ended up with me becoming a teacher in a school where we really, really valued people's migration stories. I taught in a high school in my twenties and thirties, and the school was in Brooklyn. It was called El Puente Academy for Peace and Justice and our first experience with all of the students, all the ninth graders and when they came in was for them to tell their story. The whole ninth grade theme was “Who am I?” They're going to tell their story through self portraits, through mapping their family tree, to doing family interviews…finding out their financial story, all kinds of stories. And they make a book about their lives, about themselves, a “Who am I?” book. I was able to see how that can be transformed through an educational setting in the U. S. And I wish I would have had that kind of experience at five. And those kids should have had that at five, and they shouldn't have had to wait until they're fourteen to be valued in that way. So, I think it shaped my journey. So I eventually became a teacher and was able to offer, be a part of something that helped others to tell their story.

Vidhya Manivannan

My name is Vidhya Mannivanan and I live in New Jersey… Roxbury township and New Jersey. I'm an Eela Tamizh… I was born in Eelam. You know, I was a kid and then we fled to Denmark. The Danish would never call us Sri Lankan… they would use the Danish word for Tamil. People who sought asylum there… had the freedom to represent Tamil Eelam… being Tamil. In the US, I kind of let people dictate my identity because it's hard for people to place, not even like they can look at you and be like, "Oh yeah, yeah, you're from Sri Lanka” even though I don't identify myself as Sri Lankan or from Sri Lanka… And then because I think for America like, it’s like it's either Black, white, or Latin. And then some people can be identified as South Asian… But then there’s India. But some people don't have that particular South Asian…typical South Asian look. Which doesn't necessarily exist because we all look different, but it’s what they think an Indian looks like or what they think a South Asian looks like. And then I kind of started questioning my identity when I was sixteen, because I was always Tamil in Denmark. Like I knew I was Tamil. And it was between Tamil and Danish, I wanted to be like the Danes because that's what I was surrounded by. But I knew that I was Tamil… I never claimed to be Danish or anything like that, I was proud of being Tamil. But at the same time, I was influenced by the Danish culture. So it's like kind of steering away from Tamil culture to fit in. But in the U.S. it was a new experience for me to figure out my identity and I kind of struggled. Even more than that, I was already struggling as a teenager with my identity in Denmark. Being a brown person, a brown girl… then moving to the U.S. I was surrounded by South Asians. They called me, ‘desi’ and I had never heard that term before. And I thought, oh, okay. That describes all South Asians. And I was okay with them calling me desi, but I never really identified myself as desi because that's not like a word that was familiar to me. It was the exposure to my community and [those] who had been decolonizing before I did, that helped me understand my Eela Tamil identity.

Personally, not a capitalist at all…I never, I never in a million years thought that I would have a small business. But… I feel like my dad's side of the family, they were business people, traders and stuff like that. So I think it might be something that I have in me, but I think this whole thing is not something that I planned… I didn’t see myself coming this far. So five years ago or more, I decided that I wanted to do this. My cousin's wife and I, we started researching how to make soap…we would go to stores that had essential oils and would smell and try to figure out scents … And, you know, I was working full time and I never had time to actually plan this or even try it out. So through the pandemic, I ended up having so much time. I ended up doing things that I've been wanting to do, maybe for the past twenty years. I finally have the time and I was just like, “Okay, I'm going to make soap.” But before that I've been interested in using organic skincare products on myself. I stopped using products with a lot of chemicals… I would always read the labels to find things that are good for our skin and hair. And I also worked at a Lush for a bit. And so I got to learn about handmade skin care products…when I was training, they were teaching me about all these ingredients and so on. A lot of [the ingredients] were Tamil, and it was like white women teaching me about like Tamil ingredients. And I'm like, “What is going on?” I'm learning about my ancestral ingredients from a white person. My Ammamma is very well [versed] in herbology. When I was in Eelam, we were walking and she would stop and be like, “Oh, this plant is good for this,” and collect plants here and there. And she's always been that person…you’d be like, “Oh, I think I'm going to get a scratchy throat. I think I'm going to cough, or I'm going to get the flu or whatever.” She’s like “Okay, drink this.” She always has these concoctions and they work. [I thought] this is magic and this is beautiful…why aren’t we practicing these things? This is a thing [from] the past and we're like leaving [it] behind and it's going to be erased if we're not going to continue. Just like all of it just fell into place because of the pandemic.

I ended up making some soaps and I put it out... saying, “Hey guys, I made some soap!” And then, I got so many different orders… I didn't even have a brand that I know… how this was going to go… no shipping packaging or anything. But I think from there on I had to like, kind of figure out from the business aspect of what needed to be done. And I felt like my whole identity: me as a Tamil person, nationalism, ancient Tamil history, my ancestral knowledge that my Ammamma has taught me… I started to put everything together. This is made for Tamil people, because I wanted to connect to my ancestors, my language, my history and all of it…always, through anything. Because it has been taken away from us, through colonization, Aryanization, and Brahminization…now through Sinhalization and with the whole context of Sri Lanka. So this is one of the ways for me to preserve our identity, our language, history, religion and herbology. I think it's one way of discovering history.

So far I have eight soaps and [eight] have Tamil names. I have a soap called Kali karuppusamy… like the goddess, Kali who has dark skin...they’re a Tamil god that, I would say, they’re one of those forgotten gods that people… when you go to temple you have Vishnu and you have all the Aaryan gods. I wanted to bring the hundreds of Tamil gods that have been forgotten back…I want to have these conversations. I want it to be like self discovery and learning and I want other people to experience that through [my products], it wasn't like a master plan. I wanted to use organic skin care and I want to learn more about our ingredients. And then while I was learning, I decided to incorporate that. But it was more like a hobby that kind of ignited interest from other Tamil people. I mean, it feels really good [that people are buying products]. I'm not making so much money to be one hundred percent reliant and economically on the business. But I'm hoping that I can build it that way…if not, it's just going to be like a part-time, side thing. So we'll see where it goes… but it feels good with the support that I have had throughout the world. Like I’ve shipped to Montreal, Toronto, and then throughout the U.S.…then UK and Australia. That was the first shipment. Then, recently I shipped to France, Switzerland, Denmark and Norway. And then people from Singapore also ordered and I shipped another box to Australia and New Zealand. I get to map out where everyone lives and where the interests are coming from. And it’s not just about making money…it's not just about, “Oh, these people are like paying me for my soaps” or anything like that. The interest… they understand what this whole brand that I've created stands for. I didn't just create it because I wanted to make money…I created it to preserve our identity. And people being excited about that and willing to support it…because of these [features] from our cultural identity. It makes me really happy to see that support and also to see there are more people who care about being Tamil and who care about preserving our identity. People who understand me. I think that's something that I struggled with my whole life… to have an identity. To have to ask these questions like, “Who am I?” I feel like [that question is] being answered or it's been answered, in particularly through this… it’s been confirmed.

Vinsia Maharajah

My name's Vinsia Maharajah and I'm living in Scarborough, Ontario, Canada. I generally define [my ethnicity] as just Tamil. But if it's like within a multicultural space, I'll say Tamil and South Asian, or I’ll say Canadian Tamil. Depending on where I'm speaking or where I am, it depends on the context of where I am. I feel like it's changed over the years, especially as I'm learning more stuff about what happened back home and history… as well as my family opening up about their stories. My identity definitely changed, I used to identify as Sri Lankan until probably middle school. Like I would say, “Yeah, I'm Sri Lankan.” And I wouldn't necessarily say I'm Tamil, I’d say I’m brown or I’d say South Asian... I had to say Brown or Canadian or Sri Lankan. And then as I got into high school and obviously as things escalated back home, it was important to make the distinction between what you identify as. Before I would just say, “Oh, I'm a South Asian or my parents are from Sri Lanka," just so people wouldn’t ask me any questions. But then in the last few years, I realized that it's important to answer and have those discussions. If I'm erasing the possibility of that… Why would I do that to myself? If I say I’m Tamil, and someone's like, “Oh, what is that? I thought you were Sri Lankan” And it's like “No, no, I'm not. Let me explain why.” And then you explain to them that there's some people that don’t identify as Sri Lankan who have ancestors from there. Obviously things like war and trauma have definitely changed my perception on identity. I personally think that Tamil is borderless, it's an identity that can’t be defined by borders... And I feel like it is so important to throw away the borders because the borders weren't there before the culture was, culture existed before the borders. Colonizers walk in and go, “Hey! This is a nice place to put a border!” And then we kinda refer to that, even in historical contexts, when I see even in history content or people to say ancient India - and it’s like fam, India didn't exist in that time period. How can you say ancient India? You can't say that, like it doesn't make sense. Look at Sri Lanka, there's always an argument of who was there at first...that’s always an argument and there's always something there. But in different Tamil historical books and even Sinhalese historical books there's similar crosslinks, they have worked together, they have traded or fought against each other, … they have coexisted.

I went to Sri Lanka…so there was a time where we were on the East coast, and I wanted to see the sunrise on the shore so bad, but my mom wouldn't let me. I was really mad at her, but the driver Uncle, he took me to the shore. He saw I was really mad, I was so grumpy. And he took me to the shore… and we just walked down there and just looked. And I was just like, “Oh my god!” I just ran to the ocean and just looked and sat there. And then he went off to the fishermen who were bringing their boats and they're Tamil. So we just kind of sat there and talked about, “Neenga ethina manikku neenga poninge? (What time did you go?) Entha meen pidicheenga! (How many fish did you catch?)” Little things like that....I also took some pictures, “Meen padam edukalama? (Can I take photos of the fish?)” They’re just laughing, “Enna meena padam edukaporigala (What, you want to take photos of the fish?)” And so they let me take pictures of the fish in the boat, and just things like that… that’s what I want to see, like, I don't want any of my privilege taking up the space of their stories. Respect, being aware of my privilege as well. In terms of being a woman, yeah, I'm struggling a little bit compared to the fishermen as men, but as fishermen they're facing so much environmentally, economically, identity wise. They have more struggles…they have even more issues that intersect. Basically what they're going through, versus me, where I have a comfortable safe home. I don't have to worry about environmental factors that much, though I should, about the future. As a person who's been through intergenerational trauma, PTSD, war related things it makes me a lot more sensitive to what's in front of the lens [as a photographer] and who's behind the lens. Versus people… who may not have experienced being stopped by the army or being traumatized like that, or harassed like that. Maybe they have other trauma or whatever, but it's just necessarily when you look at privileges and have a lot more privileges. [My mom’s] dad was a photographer, Ammamma painted some and she helped in photography. And there's a point where after my grandfather went missing [during the ’83 Riots], things got really bad, and she had to break rocks to make _ living. And some professor took a picture of her, and it was so messed up seeing the caption saying, “a family in poverty making a living by breaking rocks.” And this was a Tamil professor, for his documentation. I'm glad he did that. It was very insulting to see it, but I realize it’s a struggle that they went through. And it was, it was really difficult to process that they were that poor at that time…they had to deal with the war and poverty because my grandpa was missing.

I was born in Scarborough, Ontario, Canada. Everytime I go to Sri Lanka I feel like I'm home. I hate that country so much…politically, governmentally, all the oppressive powers can go to hell. But other than that, it's home. It's a place I can feel like all my family's here…when I went to the temple and in [my dad's] village, everyone looked like everyone! It’s so weird! Imagine going to a temple where everyone looks like some version of your dad or your dad's cousins. It was so weird… so trippy! But I also feel the motherland connection in South India. Especially in Tamil Nadu… I felt like I was going home. Again, that same feeling I had in Jaffna I had there, and I was shocked. I was like, “Yeah, I was just a touristy little binch. Let's go to the temple.” Once you're there and you're like, “Oh my God!” You feel like you've been there before. You feel like you've been on the land before. Like it's such a freaking crazy feeling… I don't know how to describe it. Someone that I'm related to lived here…some ancestors' home. Someone was here. Or maybe some of my ancestors visited here. But I definitely felt like…I had chills, just walking into the temple. It was a hot day and I had chills. And I was like, it's like someone was here, like someone was here. I feel like someone I know is here. It's like there's no place in Canada that I would feel that frickin spine chill that I do in just Jaffna or temples in India.